I cannot believe that I am already writing my final blog for this module; it has gone incredibly quick and I feel a pang of sadness knowing that we will no longer be spending our weeks writing and commenting on each other’s work.

Before I began this module, I was a novice blogger at best. Whilst I consider myself computer savvy to a certain degree, I had never before written a blog. Being given the freedom to express my ideas and discuss research and theory on my own page, without having to think about whether my work is relevant to the learning outcomes or if it is what the lecturer expects has been a refreshing educational experience for me. At many points during my degree I have become accustomed to take what I am given; learn what I am taught; rehearse what I have read. Therefore, it is understandable that during the first couple of blogs I felt ill-equipped and frustrated; my scaffolding had been taken away and I found it difficult to find a direction on my own two feet. Looking back at the initial few weeks, I understand now why I felt like that. Never before had I been handed such an opportunity to be autonomous in what I would learn, and this made me nervous. What if I learnt the wrong thing? What if Jesse didn’t agree with what I wrote? Now I see that these questions were irrelevant, because no matter what psychological concept I explored or educational method I discussed, I was still learning.

What have I learnt?

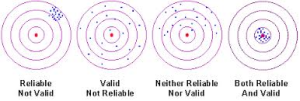

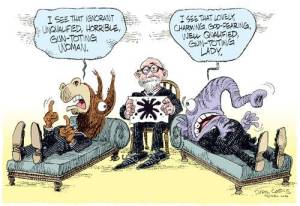

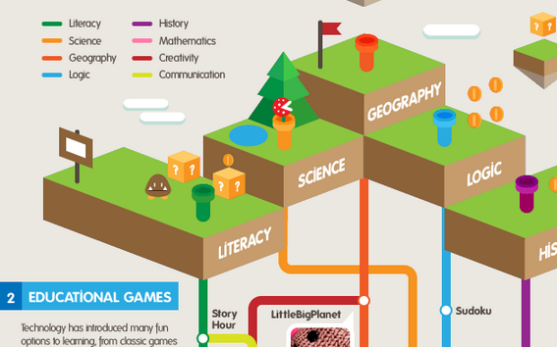

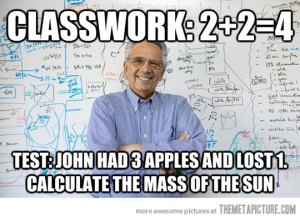

I will begin literally. I spent my weeks blogging about grades. I discussed the effects that grades have on motivation and creativity, and explored the similarity of grading systems to game play. Finally, I evaluated the extent to which grades are valid and reliable measures of student learning. I have come to the conclusion that grades are NOT a necessity in education, but a practicality, because as humans, we like to categorise and have become overly reliant on quantifiable assessment and measurement. Even in my synthesis blog, after all the evidence I had presented against the use of grades, I still had to argue that I couldn’t see it changing, when in reality, grades will have to change in order for us as students to be able to present and demonstrate accurately our capabilities and accomplishments. Is it accurate and fair to reduce all my pieces or work, all my learning, reading, speeches, effort, accomplishments and achievements into one ultimate degree classification? Honestly, I think the answer is no. Jesse commented on my previous blog that I was still missing the point arguing that grades have to be used. They don’t! They are only continued to be used because it is the done thing. Not necessarily the best way, the right way, or the fair way, but the done thing nevertheless. I will be interested to see how grading systems will change in the future; I only hope that educators will begin to take notice of the research and evidence out there, and realise that it is not fair or truthful to evaluate a student by simply assigning them a letter grade or a percentage.

Secondly, I would like to comment on what I will take away from this module, other than the topics I have blogged and read about. I have learnt that it is possible to learn autonomously, without the continuous guidance and instruction of a teacher. I have realised that learning does not end when the lecture has finished, and that it is wrong to think that I should only learn what my teacher has included on a PowerPoint slide or what I have been told will be on my final exam. Furthermore, I have discovered that autonomous learning is more enjoyable than I ever imagined it would be (with the added bonus of no final exam!!!) If I were to count the hours I have spent researching and reading and then blogging, discussing, commenting and debating, I realise I have dedicated far more time to this module than any other module during my whole degree. Most importantly, I have been given the freedom to learn what I choose, without boundaries, and without having to conform to the rigid learning outcomes that stipulate what I must learn in order to do well.

Finally, I would like to thank Jesse, for sitting back and observing us developing our own ideas; for not spoon feeding us, but for giving us an opportunity to learn what we are interested in, and for organising the most enjoyable module of my undergraduate degree.

Thank you Jesse, and thank you to everyone who has taken the time to read my blogs and comment on them.

Emma